Two years ago, at 44 years old, Gregory Nash was living the life some people only dream about.

A musician since the age of 14, he was well-known in the local entertainment scene, playing drums with bands throughout the Capital Region and beyond. Often called a “musician’s musician,” Nash was someone others in the musical world looked up to for his commitment, standout talent, and unbelievable work ethic.

Sadly, on March 8, 2017, that dream turned into a nightmare. Upon waking, Nash could tell something was wrong. While getting ready for work, he remembers blacking out several times, yet he still got into his car to drive into work, hitting a parked car along the way. Once at work, his coworkers thought he might have been drinking, even though he had been sober for 20 years. After some time, his boss brought him to the St. Peter’s Hospital emergency department, where doctors determined Nash had experienced a severe stroke and suffered a traumatic brain injury. In addition to problems with movement in his right arm and hand, Nash was unable to speak.

After a week at St. Peter’s Hospital, Nash spent another eight days as an inpatient at Sunnyview Rehabilitation Hospital, before starting outpatient therapy. With physical and occupational therapies, he worked to regain function of his right arm and hand. But speech was another matter altogether.

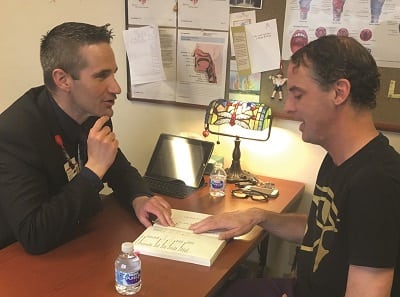

“When I first met Gregory, he was unable to make any sound at all,” said Jonathan Brendese, MS, CCC-SLP, CBIS, a speech/language pathologist and certified brain injury specialist at Sunnyview. “He was the most severe case I had ever seen in my eight years in the field.”

Although Brendese doubted Nash would ever speak again, the experienced therapist wasn’t going to give up that easily. “While we might not be miracle workers, we are agents of hope,” Brendese said. “I was going to do everything I possibly could to help Gregory speak again.”

Nash suffers from aphasia, apraxia and dysarthria — the three main communication conditions faced by individuals after having a stroke. Aphasia is impairment in the ability to use or comprehend words. With apraxia of speech, the individual has trouble saying what he/she wants to say correctly and consistently. Dysarthria happens when a stroke causes weakness of the muscles used to speak, such as the tongue, lips or mouth. It can affect the pronunciation of speech sounds, the quality and loudness of the voice, and the ability to speak at a normal rate with normal intonation.

Brendese, who coincidentally also enjoys playing the drums, searched for a sound Nash might be able to make. As it turned out, it was the “M” sound, a bilabial consonant sound that is made with both lips. With determination and hard work — and the use of a mirror, visual cues, and lots of repetition — Nash said his first word since the stroke: “Mom.”

Now, a year later, Nash has come a long way, although he still has trouble with some sounds. He continues therapy with Brendese two or three times a week, and is working on his “R” sounds.

“Gregory is amazing, he’s the hardest worker I’ve ever seen,” Brendese said. “He has never missed an appointment and is always on time.”

That fierce determination continues with his music. With his right arm and hand about 90 percent back to normal, Nash has worked hard to regain his drumming skills and after months of patience and practice, he is playing again. In fact, in late March – a year after his musician pals played a benefit for him — Nash played in another benefit, one he helped organize. Called “One Stroke Roll: A Benefit for Sunnyview Stroke Victims, Celebrating Gregory Nash’s One Year Strokeversary!,” the event, held at The Hollow in Albany, attracted 175 family members, friends, and fans, and raised more than $3,500 for Sunnyview’s post-stroke program.

Brendese said he was not surprised Nash wanted to give back to others: “Gregory’s musical talent is phenomenal, his perseverance is unbelievable, but most of all, he’s just a great human being.”